Fungi are slowly but surely inching their way into the collective consciousness.

Whether it’s in the realm of health, sustainability, or spirituality, our inconspicuous fungal friends are providing solutions to some of mankind’s most pressing issues and changing the way we think about them - and ourselves.

Recent discoveries and novel ideas about fungi are spreading like, well, mycelium (the underground organism from which mushrooms sprout).

The illuminating Netflix documentary Fantastic Fungi has been seen by millions, while the rise of figures like Paul Stamets and the success of books like Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake has spawned a new generation of mycophiles.

And I’m one of them.

So with that in mind, here are 7 profound lessons I’ve learned from studying fungi and mushrooms.

1. Cooperation is a strength

There is an organism called a lichen. Well, it’s actually two organisms (a fungus and an algae) that have entangled themselves so tightly that they are effectively one.

This remarkable relationship has occurred as a way for both organisms to take advantage of their partner’s unique abilities - the algae can photosynthesise but the fungus can’t, and the fungus can absorb nutrients from the soil but the algae can’t. This allows lichen to live in environments that individual fungi and algae couldn’t.

In effect, they are better together than they are separate. The whole (in this case, a lichen) is greater than the sum of its parts.

There is an important lesson here. And it’s this: By cooperating, whether with other people or species, humans have the opportunity to be something we couldn’t be on our own. We can solve problems we couldn’t on our own.

In fact, we are already cooperating with fungi in many ways. Think about the fungal population in our guts (the gut microbiota), for example, which play a big role in our body’s immune response, inflammatory response, and even our neurological health. Or consider penicillin, alcohol and bread - all made with help from a fungus.

We’ve made a start, and over time we will discover more ways to cooperate with others, including fungi, in order to advance both contributors.

For some idea of what fungal collaborations may look like, consider Paul Stamets’ discovery that mushrooms extracts can help save the bees, the ability of mycelium in soil to store carbon, and fungal textiles that offer biodegradable alternatives to plastic.

By joining forces with fungi, we can both help create a healthier world where we both can continue to thrive for a long time.

2. Decentralised networks are incredible problem solvers

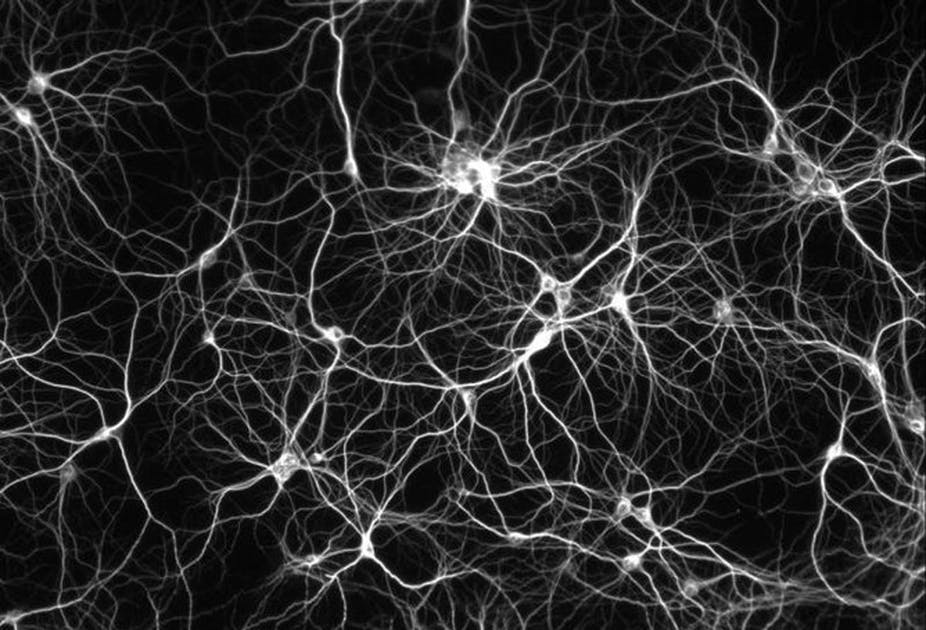

Mycelium grows in a decentralised network. This means it has no one point of control - like our bodies do in the form of our brain. This lack of a central authority makes mycelium networks highly resilient to attack and highly adaptable to changing environments. Distributed authority allows mycellium to become incredible problem solvers.

Paul Stamets explains it like this: “Interlacing mosaics of mycelium infuse habitats with information-sharing membranes. These membranes are aware, react to change, and collectively have the long-term health of the host environment in mind.

“The mycelium stays in constant molecular communication with its environment, devising diverse enzymatic and chemical responses to complex challenges.”

Many of these ‘diverse enzymatic and chemical responses to complex challenges’ are unique compounds that can also be used by humans in inventive ways. For example, the potent psychedelic compound psilocybin which is expressed in hundreds of mushroom varieties, is a chemical response that evolved millions of years before humans even existed.

Other decentralised networks that spring to mind include the neural networks in our heads (our brains), the internet, and Bitcoin.

By relying on distributed authority, decentralised networks are constantly evolving based on feedback from their environment. The results of this can be seen in fungi’s survival over multiple extinction events, humans’ flourishing over the last few thousand years, the incredible growth of the internet and its importance in the modern world, and the initial success of Bitcoin (13 years so far).

3. Everything is literally connected

If you stand in a forest, you will see many individual trees and plants. Under the ground, however, all these plants are connected together by networks of fungal mycelium.

The term “mycorrhizal relationships” describes this mutual symbiotic association between a fungus and a plant root system. This relationship, which sees plants providing fungi with carbon-based compounds and fungi providing plants with nutrients like nitric oxide from the soil, enhances the health of the ecosystem as a whole, making it more resilient and adaptable.

It got me thinking about the invisible connection between humans, other animals, plants and fungi. Just as with mycorrhizal connections, just because we don’t see these connections easily, does not mean they’re not there.

By considering these invisible connections and recognising our own place in ecosystems, we can make better decisions for the health of the whole.

4. Death is necessary for life

Fungi are responsible for breaking down all organic matter in order for it to be reused, whether by itself or other organisms. Fungi are the bin men and recyclers of the forest, without whom there would be layers of dead organic matter everywhere.

They do this by releasing enzymes to break down the material - think dead animals, plants, and even rock - after which the nutrients released can be absorbed.

Before fungi were around, this dead matter did not decay. Instead, it would be compacted by more and more dead matter over millions of years to eventually become the ground oil that we rely on so much for energy today. We are able to harness the stored energy in oil because it was never broken down and released by fungi.

Fungi represent an important part of the cycle of life. They act as the passageway between death and life. They continuously break down the old in order for the new to be birthed.

Fungi have taught me that while our lives my be transitory like that of the mushroom, it doesn’t matter because there is an underlying source that we come from that is continuous and connects all life.

5. Fungi are everywhere

Fungus and mould are gross right? Well, unbeknownst to most people, fungi are everywhere.

Between tens and hundreds of species of fungi live on any given leaf you might find in your garden. In fact, no plant has ever been found in nature which does not have fungi in its leaves and shoots.

You have yeast all over your body, especially in the lining of your ears and in your nostrils. They’re even in the air, floating around you, being inhaled by you every few seconds. Fungal spores are the largest source of living particles in the air.

I guess this one isn’t so profound, but it is interesting.

6. Soil is the gut of the world

If all fungi were wiped out in a forest floor, the trees and plants would not survive and, subsequently, the animals would starve. The flora would struggle for nutrients and become prone to disease, just as humans would if it weren't for the trillions of cells, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi in our gut.

As mentioned earlier, the human microbiome plays a huge role in keeping us healthy, regulating our immune system, our inflammatory response, and our neurological health.

In this sense, the forest floor and soil can be seen as a sort of gut to the planet. Keeping both the soil and our gut micropopulations well-balanced, healthy and fed will improve the overall health of our bodies and our forests.

And just as antibiotics can achieve short term goals (stopping an infection) by disrupting the microbiome of the gut, pesticides and other pollutants achieve similar short term goals (stopping an infestation) while disrupting the microorganisms in the soil. Both have long-term negative consequences.

This fungal view of ecosystems can help us to appreciate the diverse populations of microorganisms that support the long term health of our forests and our own bodies.

7. Individuals are actually ecosystems

We humans think we’re individual people, but we are made up of millions of organisms that work together, cooperate, compete and fight one another.

When we consider that all life is based on these intimate connections, then it becomes clear that we can't be regarded as individuals. Our bodies are actually ecosystems.

Summary

We can learn a lot from fungi

You see, humans, with all their intelligence and advancements, are still a part of nature. Thus, by studying nature and its patterns, we can learn about our own nature and patterns.

We know a fair bit about other animals and the plant life on our planet, but we know comparatively little about the kingdom of fungi - which is in fact more closely related to humans than to plants.

By studying and learning about fungi - the literal foundation to all almost all plant and animal life - we get a deeper understanding of nature that can aid us in living healthier, happier, and more sustainable lives.

What have you learned from fungi?