For years, researchers have known that chronic pain and depression often appear together, like two shadows feeding off one another. But why they’re so deeply entangled has remained a mystery.

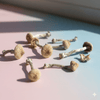

Now, a new study from the University of Pennsylvania offers the clearest view yet of what’s happening in the brain - and how psilocybin, the active compound in psychedelic mushrooms, might help break the cycle.

Published in Nature Neuroscience in October 2025, this research maps the precise neural circuits where pain and mood overlap, and shows how psilocybin can recalibrate them in a single dose.

Let’s unpack what the scientists found, how they discovered it, and why it could reshape the future of pain medicine.

The Pain–Depression Loop

Chronic pain isn’t just physical. It rewires the brain’s emotional centres, making it harder to separate bodily discomfort from psychological distress.

Over time, this creates a feedback loop: pain fuels low mood, and low mood amplifies pain sensitivity.

Traditional painkillers target pain receptors, not the brain’s emotional circuitry. Antidepressants, meanwhile, can take weeks to work and don’t address physical pain.

The Penn team asked a radical question: What if one psilocybin could treat both quickly, safely, and without addiction?

The Experiment

Using two models of chronic pain in mice - one involving nerve injury, the other inflammation - researchers administered a single dose of psilocybin.

The results were remarkable:

-

Pain responses dropped sharply.

-

Anxiety and depression-like behaviours eased.

-

These effects lasted for up to two weeks, which is far longer than the drug stayed in the body.

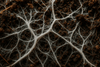

To understand how, the team tracked neural activity using two-photon fluorescent microscopy, an imaging technique that lets scientists watch living neurons fire in real time.

They observed that in animals with chronic pain, neurons in a region called the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) were firing excessively - a pattern linked to emotional distress and pain perception.

After psilocybin, this overactivity normalised. The brain, in essence, found its rhythm again.

The Brain’s Dimmer Switch

Most drugs work like a light switch. They flood or block a receptor completely. Psilocybin, by contrast, acts like a dimmer switch on serotonin signalling.

It partially activates 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors, key gateways that regulate mood, sensory perception, and meaning. This gentle tuning appears to calm overexcited circuits rather than shut them down, allowing the brain to self-stabilise.

When researchers injected psilocin (the compound psilocybin converts to in the body) directly into the ACC, it produced the same relief as a full systemic dose. But when they injected it into the spinal cord, nothing changed.

This was the key insight. Psilocybin doesn’t treat pain where it starts in the body. It treats it where it hurts most: in the brain’s interpretation of suffering.

The Implications for Healing

This study reframes how we think about both pain and depression. Instead of seeing them as separate disorders (one physical, one emotional), it shows they share a common neural network. And by modulating that shared network, psilocybin appears to bring relief to both.

The implications ripple far beyond chronic pain:

-

PTSD, where traumatic memories keep circuits locked in fear.

-

Addiction, where craving hijacks reward loops.

-

Post-surgical pain, where physical and emotional recovery are deeply intertwined.

Psilocybin may offer a non-opioid, non-addictive therapy that restores connection rather than suppressing sensation.

As Dr. Joseph Cichon, the study’s lead author, put it:

“Psilocybin may offer meaningful relief by bypassing the site of injury altogether, modulating the brain circuits that process pain, while lifting the ones that help you feel better.”

What’s Next

Next, the Penn team plans to explore:

-

Optimal dosing strategies: How small can a dose be and still produce change?

-

Duration of effect: Can the brain “learn” from the reset?

-

Long-term safety: How repeated exposure shapes neural plasticity over time.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, a sign that psychedelic science is moving firmly into the medical mainstream.

The Bigger Picture

For centuries, humans have turned to mushrooms in search of healing the body, mind and spirit. Now, the science is catching up.

This study doesn’t claim psilocybin is a miracle cure. But it does suggest something profound: that the same compound capable of opening the mind might also help free it from the circuits of suffering.

At Mushies, we see this as a reminder that the mind and body are one, that we can change our brain and minds, and that true healing begins with reconnection rather than suppression. And all it takes is a mushroom to remind us how.