Mushrooms usually make headlines for the wrong reasons. Poisonings, toxic species, that sort of thing. But Kumar Biswajit Debnath, a researcher at the University of Technology Sydney, wants us to look past the mushroom itself and focus on what's really interesting: the stuff underneath.

After diving into what's happening in this space, I'm convinced we're watching something transformative unfold.

Meet Mycelium: Nature's Hidden Network

The thing most people don't realise is that the mushroom you see is just the fruit. The actual organism is this incredible white thread network called mycelium, spreading through soil and wood like nature's own internet. These threads, called hyphae, are tubular structures that intertwine to form a lightweight, lattice-resembling foam.

According to Debnath's work, this underground web might actually help us tackle some pretty massive climate and waste problems. Think about it. Mycelium is literally everywhere, including forests, compost piles, and dead wood under your feet. It's nature's recycler, breaking down organic matter and turning waste into nutrients. A single network can stretch for miles. We just never see it doing its thing.

A Living Material

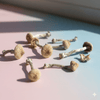

Debnath and researchers like him are using mycelium as a kind of living construction material. The fungi naturally bind to whatever they're eating (sawdust, straw, agricultural waste) and basically glue it all together as they grow.

This is exactly what Ecovative, the company that pioneered mass mycelium farming, discovered back in the day. Founders Eben Bayer and Gavin McIntyre mixed mycelium with agricultural waste like corn stover or hemp, put it in a mold, and let nature do its thing. In just four days, you've got a rigid structure. Grow it for two more days and it gets coated with a soft, velvety layer. Heat it to stop the growth, and boom, you've got a building material that required no machinery, no plastics, barely any energy.

Debnath has some pretty cool examples from his own work. Like composite panels made with Australian Reishi fungi and local waste like sugar mill bagasse, golf course mulch, and hemp. The applications are diverse - packaging alternatives to polystyrene, synthetic insulation replacements, acoustic panels, even leather-like materials.

From Lab to Real World: It's Already Happening

The scale of what's possible is kind of mind-blowing. In a recent video, science educator Matt Ferrell (from Undecided with Matt Ferrell) visited Ecovative's indoor farm where they're growing what they call "AirMycelium". These are pure mycelium sheets harvested from oyster mushrooms. On just one acre of land, they produce three million square feet of material each year. That's nearly 700,000 square metres per hectare.

And it's not just experimental anymore. In 2025, a 316-unit affordable housing complex called The Phoenix is opening in West Oakland, California, with exterior cladding made from mycelium panels. These are 36-foot-long prefabricated panels grown from Ecovative's mycelium-and-hemp blend, then encased in a fiber-reinforced-polymer shell. They'll serve as thermal insulation, cutting energy costs while being naturally fire-resistant and carbon negative.

But wait, it gets weirder. That same mycelium can be compressed and embossed to create leather that luxury brands like Hermès are using in handbags. Or sliced thick, brined, and fried to make bacon that's apparently on shelves in over 1,400 stores. Ferrell tried it and said it passed the sizzle test. MyBacon is now the fastest-growing plant-based meat in the northeast US.

The Reality Check

Now, Debnath is refreshingly honest about the limitations. These mycelium-based composites aren't replacing bricks or most plastics anytime soon. They absorb humidity unless treated. They decay outdoors without protection. And getting consistent, large-scale production from a living organism is tricky.

His research focuses on making these materials more durable for building applications, especially for passive cooling. They're experimenting with natural reinforcement using hemp and flax, protective coatings from natural waxes and oils, and even using AI to optimise the growing conditions for more uniform density and better structural performance.

Some experiments fail. Coatings trap moisture, certain fibres slow growth, materials become too brittle or spongy. But each failure teaches us more about how fungi build their networks, and how we might guide them to build stronger ones.

Why This Actually Matters

What gets me excited about this isn't that mycelium will replace concrete tomorrow. It's the fundamental shift in thinking.

For decades, we've asked: "What can we manufacture? What can we machine or mold?" Now researchers like Debnath and companies like Ecovative are asking: "What can we grow?"

The environmental math is compelling. Mycelium grows at room temperature in the dark, requiring minimal energy and water. It upcycles agricultural waste into versatile building blocks. When you're done with it, it composts back into the soil instead of sitting in a landfill for centuries. It's the essence of a circular economy. Products that aren't just biodegradable, but regenerative.

Compare that to traditional leather tanning (chemical-heavy, water-intensive) or polystyrene packaging (petroleum-derived, basically immortal). Mycelium leather produces half the emissions of conventional leather and costs a fraction of the price. It breaks down like real leather instead of hanging around like plastic.

The Weird Frontier

The applications keep getting stranger and more ambitious. NASA is exploring whether living mycelium could be brought to the moon or Mars to grow habitats. At Cornell University, researchers are using mycelium's natural light aversion to create living sensors for biohybrid robots that could monitor soil conditions for more sustainable agriculture.

There's a glamping cabin in the Czech Republic designed to look like parasol mushrooms where literally everything (the wall cladding, insulation panels, even the stools) is grown from mycelium.

In Namibia, an initiative called MycoHAB built a one-bedroom home using mycelium bricks they claim are stronger than concrete. In France, a startup is making surfboards with mycelium cores. In the Netherlands, biodegradable coffins. In Italy, acoustic wall tiles.

The Long Game

Debnath envisions hybrid building components - part grown, part engineered - where mycelium provides insulation or acoustic performance inside a stronger outer shell. It's not about fungi replacing everything; it's about finding the right niches where living materials make sense.

The mycelium-based packaging market alone is already valued at nearly $85 million and projected to reach over $200 million by 2034. Ecovative just secured $28 million in funding to triple production capacity. Major fashion brands are lining up for their leather. The material is already on construction sites and store shelves.

We're still early days. Standards and regulations take time. Outdoor durability is a real hurdle. Not every coating works, not every fibre cooperates. But the pace of discovery is fast, and the potential is enormous.

The Bigger Picture

What I find compelling about all this is the elegance of the solution. Mycelium does what it's always done: digest organic matter, bind materials together, grow in the dark. We're now learning to harness those natural abilities in new contexts.

It's not a magic solution. It won't replace all metals, concrete, or high-performance plastics. But it doesn't need to. It needs to be better than petroleum-based foams, chemical leather tanning, and single-use plastics. And in many cases, it already is.

The mushroom might be what we notice, but it's that hidden fungal network underneath that could revolutionise how we make things. From the clothes we wear to the homes we live in, from the packaging that protects our electronics to the sensors in our robots.

These hidden fungal threads might be one of the most exciting materials to come along in decades.

Based on research by Kumar Biswajit Debnath, Chancellor's Research Fellow at the School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney, and reporting by Matt Ferrell of Undecided