In a groundbreaking study published in Nature, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have unveiled the astonishing effects of psilocybin on the human brain.

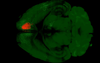

Using functional M.R.I. scans, they recorded the kaleidoscopic brain activity of seven healthy adults who were given a single dose of psilocybin or a placebo.

The results were nothing short of extraordinary.

The scans revealed a massive, threefold increase in neural disruption among those who took psilocybin, compared to those who received the placebo.

This disruption occurred in parts of the brain responsible for introspective thinking, such as daydreaming and self-reflection.

Interestingly, these areas help define our sense of self, and the study showed that psilocybin seemed to "dissolve" this sense of self, at least temporarily.

But what's even more fascinating is that the effects of psilocybin persisted long after the drug had left the individual's system.

The brain scans showed that while the overall activity returned to normal, there remained a small but significant change suggesting that the drug's effects were still present.

This has profound implications for the use of psilocybin in therapy, particularly for mental health disorders such as depression, addiction and anxiety.

So how does psilocybin achieve these remarkable results?

Dr. Joshua Siegel, a neuroscientist and lead author of the study, explains that the drug disrupts the brain's default mode network, which is typically active when we're not focused on anything in particular.

This disruption leads to a chaotic, unsynchronised firing of neurons.

The neural disruption caused by psilocybin is believed to be a driving force behind the therapeutic effects of the drug, as it can lead to neuroplasticity - the brain's ability to form new connections and ways of thinking.

This disruption can help break destructive thought patterns and promote lasting changes in the brain, which may contribute to improvements in mental health and well-being.

Ceyda Sayali, a cognitive neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University, points out that this phenomenon lessens when participants are asked to focus on their surroundings, a process known as grounding.

The sudden shift from the psychedelic state to reality is reflected in the brain scans, which show a brief calming of activity.

The study's findings support the notion that the psychedelic experience, with its intense visualisations, distortions of time and space, and detachment from self, is an essential part of the therapeutic process.

While some researchers are working to develop compounds that provide the benefits of psychedelics without the disorienting effects, Dr. Siegel believes that the desynchronising mechanism revealed by this study is required for full therapeutic effects.

As researchers continue to explore the therapeutic potential of psilocybin and other psychedelic compounds, the insights gained from this study will undoubtedly play a crucial role in shaping the future of mental health treatment.