You know how everyone's obsessed with vitamin C and vitamin E? How we're all chugging antioxidant smoothies and popping supplements like they're going out of style? Well, it turns out we might have been overlooking one of the most powerful antioxidants this whole time.

There's this compound that was discovered decades ago, studied intensely in the 1980s, and then... basically forgotten. It's called ergothioneine, and Professor Barry Halliwell from the National University of Singapore thinks it might be one of the most important molecules for healthy ageing that nobody's talking about.

The Vitamin E Problem

Let me back up for a second. The story of ergothioneine starts with a mystery: why doesn't vitamin E work?

For years, scientists knew that oxidative damage (basically, your cells getting rusty from the inside) was a major driver of Alzheimer's and other age-related diseases. They could see it clear as day in brain tissue from dementia patients. DNA damaged, proteins damaged, everything oxidised.

So naturally, they tried giving people vitamin E, one of our most powerful antioxidants. Makes sense, right?

Except it didn't work. Multiple clinical trials produced disappointing results across the board.

Professor Halliwell, who's been studying free radicals and antioxidants since 1971 (yes, he's been at this for over 50 years), finally figured out why. Vitamin E only protects one type of molecule: lipids, the fats in your cells. But oxidative damage hits everything, including your DNA, your RNA, your proteins, all of it.

It's like trying to fireproof a house by only treating the curtains.

Plus, when you take vitamin E supplements, it barely gets into your brain anyway. And it takes forever to accumulate.

Enter The Mushroom Molecule

So here's where ergothioneine comes in, and the story gets really interesting.

Your body can't make this stuff. You have to get it from food. However, you have a specific transporter just for ergothioneine. It's called OCTN1, and its entire job is to grab ergothioneine from your gut and distribute it throughout your body.

Think about that for a second. Evolution gave you a dedicated molecular taxi service just for this one compound. Your kidneys even work to recycle it back into your bloodstream instead of peeing it out. Your body holds onto it for 3-4 weeks.

Why would evolution do that unless this molecule was really, really important?

"These facts alone—specific transporter, avid retention, renal reabsorption—suggest that this compound is very important to us," Halliwell explained in a recent interview. "But despite that, it's been extensively ignored for about the past 30 or 40 years."

The Singapore Discovery

A few years ago, Halliwell's team started measuring ergothioneine levels in people's blood as they aged. Levels decline a bit with age, but nothing dramatic.

Then they looked at people with mild cognitive impairment (folks who are starting to forget things and act a bit oddly, but not quite to the point of dementia yet).

The results were stark. These people had remarkably low ergothioneine levels.

They confirmed it with Parkinson's patients. Same thing. Then they got access to a much larger dataset through Singapore's Memory Aging and Cognition Centre - 88 subjects ranging from cognitively healthy to frank dementia.

The pattern was crystal clear. As cognitive impairment increased, ergothioneine levels dropped. And when they followed people over time, those with low ergothioneine had a significantly higher risk of developing cognitive problems.

"If you have a low level of ergothioneine, it's associated with problem rates of decline," Halliwell said. The faster someone's ergothioneine dropped, the faster they deteriorated.

Low ergothioneine wasn't just found in brain diseases either. It showed up in cardiovascular disease, frailty, macular degeneration, even erectile dysfunction. The list keeps growing.

Correlation or causation?

Here's where Halliwell gets really careful, and I appreciate this about him. He's quick to point out that correlation isn't causation.

Just because low ergothioneine predicts disease doesn't mean low ergothioneine causes disease. Maybe the diseases cause ergothioneine to drop. Or maybe both are happening simultaneously for some other reason.

So how do you figure out if ergothioneine actually matters? You do experiments.

And, remarkable, there's already a mountain of research in animal models, cell cultures, and disease models showing that ergothioneine is incredibly protective. It's just that nobody had put it all together and tested it properly in humans.

Why It Works Better Than Vitamin E

Remember how vitamin E only protects fats? Ergothioneine protects everything - DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids, the whole package.

But it gets better. Ergothioneine isn't just an antioxidant. It does a bunch of other things:

- It gets into your mitochondria (your cellular power plants) and keeps them functioning properly

- It might actually promote the growth of new brain cells (neurogenesis)

- It restores long-term potentiation, which is essential for forming new memories

- It boosts NAD+ levels in mitochondria, which everyone's excited about these days

- It's anti-inflammatory

"We believe that the mechanism of neuroprotection is very likely multifactorial," Halliwell explained. "Its antioxidant properties are helpful, but the reason it seems to work so well is it's doing other things as well."

Here's a wild example. Vitamin E can only protect you once oxidation has started. But if ergothioneine really does promote neurogenesis, it's not just protecting your existing neurons, it might be helping you grow new ones.

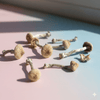

The Mushroom Connection

So where do you get this miracle molecule? Mushrooms. Lots and lots of mushrooms.

Oyster mushrooms, shittake and lion's mane are among the richest sources, but most mushrooms contain significant amounts. You also find it in organ meats and some vegetables, particularly beans, though there's a catch there.

See, humans and other animals can't make ergothioneine. Only certain fungi and bacteria can produce it. But the cool thing is many plants have relationships with fungi in the soil. The fungi give the plant ergothioneine (and probably other benefits), and the plant gives the fungi... well, whatever plants give fungi in these symbiotic relationships.

So if your asparagus grew in soil with the right fungi, it'll be loaded with ergothioneine. If it was grown hydroponically in a sterile environment, you're out of luck.

This has actually sparked a whole discussion in agricultural journals about whether our obsession with sterile, controlled growing environments might be depleting nutrients we didn't even know we needed.

Interestingly, studies in Singapore, Japan, and the United States have all found that people who eat more mushrooms have a lower risk of developing cognitive impairment, depression and even cancer. Obviously mushrooms have lots of compounds, so you can't say it's just the ergothioneine. But it's suggestive.

The Clinical Trial

About three years ago, Halliwell got funding for a proper double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in elderly people with mild cognitive impairment. They needed 150 subjects to have enough statistical power.

Then COVID happened.

"We couldn't get people into the hospital for two years," he said. "And then when we tried to restart the trial, a lot of people had disappeared or didn't want to continue."

But 18 people did complete the study. Not nearly enough for firm conclusions, but enough to see some tantalising signals.

They gave people 25 milligrams of ergothioneine three times a week (or a placebo). First off, supplementation clearly worked as blood levels went up.

They ran a battery of cognitive tests. Most were trending toward improvement but didn't reach statistical significance with such a small group. But when they combined all the tests into a global cognitive performance score, ergothioneine gave a significant improvement compared to placebo.

Even more interesting was a marker called neurofilament light protein that increases when neurons are damaged. In the placebo group, it kept rising over the study period. In the ergothioneine group, it flattened out.

"Eighteen subjects really is not enough to make clear-cut conclusions," Halliwell cautioned. "But already in this small study we're seeing indications that in a bigger study, ergothioneine will be significantly neuroprotective."

They're now seeking funding to do it properly.

Should You Start Eating More Mushrooms?

When asked about supplementation, Halliwell is careful. "I'm not actually suggesting that people should supplement with ergothioneine because we don't know what the optimum level is. What I suggest is people eat more mushrooms."

He recommends about 2-3 portions of mushrooms per week, which seems to be equivalent to the dose they used in their trial.

The European Food Safety Authority has approved up to 35 milligrams per day as safe, and several companies are already adding ergothioneine to supplements. But quality control is variable, and Halliwell always analyses products before working with companies because many supplements don't contain what they claim.

On a practical note, ergothioneine is heat-stable, so cooking your mushrooms is fine. But they analysed mushroom soup and found that the processing seems to destroy a lot of it, so fresh or simply cooked mushrooms are better.

The Bigger Picture

We've been so focused on the antioxidants we can easily measure and study (vitamins C and E, polyphenols, carotenoids ) that we completely overlooked this molecule that our bodies are literally built to capture and hoard.

It passes from mothers to babies through the placenta and breast milk. It's found in newborn babies' brains. It accumulates in your mitochondria when you exercise. So evolution clearly thinks it's important.

And yet, most people have never heard of it.

Part of why Halliwell is so excited about ergothioneine is that it represents a different approach to ageing research. Instead of trying to find a drug that fights one specific pathway or disease, they've identified a fundamental compound that your body already knows how to use, distributed by machinery that's already in place, affecting multiple systems simultaneously.

"The diet-derived compound ergothioneine is very important for maintenance of normal brain function," he concluded. "And low levels of it predispose humans to significantly increased risk of neurodegeneration and other age-related diseases."

What Happens Next

The longevity field is starting to pay attention. Research groups are now studying ergothioneine's effects on sleep, depression, Parkinson's disease, stroke, heart health, and macular degeneration.

There's even interest in combining it with other compounds to see if there are synergistic effects. Ergothioneine plus flavonoids, plus carotenoids, that kind of thing. Though testing all those combinations in humans would be prohibitively expensive, so they'll probably use stem cell models first.

One challenge is that there's huge individual variation in how people absorb and process ergothioneine. Some people with high levels are very efficient at taking it up; others with low levels aren't. There are genetic variations in the OCTN1 transporter that might explain this, though the details aren't worked out yet.

The team is also working on developing rapid blood tests to measure ergothioneine levels, because regardless of the mechanism, if you have low ergothioneine, you're going to have problems down the road.

Healthy Longevity

Yes, eat your mushrooms. Yes, let's do the science and figure out optimal ergothioneine levels. But also, maybe the goal isn't to live forever or look 25 when you're 75.

The goal is to maintain what Halliwell and his colleagues call "healthy longevity", to be one of those centenarians who's clinically fine, living their life without major illness bothering them, and then one day they just don't wake up.

As opposed to the current norm where the last 10 years of life are spent increasingly sick and declining.

And maybe this forgotten mushroom molecule is part of how we do that.

Professor Barry Halliwell's research on ergothioneine is ongoing. His book "Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine" is in its fifth edition and has been cited over 36,000 times. He was named a Citation Laureate in 2021 and is recognized as a researcher of Nobel class by Clarivate.