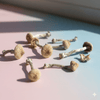

So here's a weird collision of modern medicine that nobody anticipated. Millions of people are now on GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy for weight loss, and some of them are discovering that their mushroom trips just... don't work anymore.

Joe Moore over at Psychedelics Today published a fascinating piece this week that caught my attention because it's addressing something kind of important if you're navigating the psychedelic space in 2025.

The Problem

Here's what's happening. GLP-1 medications fundamentally change how your digestive system works. They slow everything down, meaning your stomach empties more slowly, food moves through your intestines at a crawl, and absorption becomes unpredictable. And that's the point of then, because this is essentially how they help with weight loss.

But there's a catch. When you eat psilocybin mushrooms, your body needs to convert that psilocybin into psilocin (the actual active compound) in your gut and liver. If your digestion is crawling along at half-speed, that process gets disrupted.

People are reporting some frustrating experiences:

- Trips that take 2+ hours to kick in instead of the usual 45-90 minutes

- Effects that feel blunted or unpredictable

- Sudden drop-offs instead of the usual gentle comedown

- Sometimes nothing happens at all, leading people to think they're "non-responders" or that they need to redose

That last one is particularly concerning from a safety perspective. You don't want someone doubling their dose at the 90-minute mark, only to have both doses hit them three hours in.

Potential Solutions

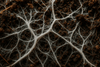

Moore reports that people in private Signal groups have been workshopping a clever workaround. What if you skip the gut entirely? One answer could be sublingual psilocin.

Instead of taking psilocybin mushrooms orally and waiting for your sluggish digestive system to convert it, you take psilocin (the already-active compound) directly and hold it under your tongue or in your cheek. It absorbs through your mucous membranes and enters your bloodstream quickly, completely bypassing the digestive bottleneck.

This isn't a new idea. LSD, DMT, ketamine and cannabinoids can all be administered this way. The benefits include:

- Much faster onset (10-20 minutes instead of an hour or more)

- More consistent dosing since you're not relying on digestion

- Higher bioavailability because you avoid that first pass through the liver

- Way more predictable for people with GI issues or medications that affect digestion

For someone on GLP-1 meds, this could be the difference between a therapeutic experience and a frustrating non-event.

But there's another approach that's way more accessible: the lemon tek.

Dr. Erica Zelfand, writing about her clinical experience working with retreat clients, describes seeing the exact same problem Moore outlines. Clients on GLP-1 drugs were experiencing slow, muted trips. Or sometimes the mushrooms wouldn't kick in for four hours, leading to some awkward situations (like one client who called a taxi home, only to start tripping during the ride).

Her solution is to use lemon juice to do the conversion work that the stomach normally does.

The lemon tek is beautifully simple. You simply soak your mushrooms in lemon juice, lime juice, or vinegar for about 15 minutes. The acidic environment converts the psilocybin into psilocin. So you're essentially drinking pre-activated medicine, and your compromised digestive system doesn't have to do the heavy lifting.

Zelfand reports being "very pleased" with thee results. Clients are happier, the experience is more predictable, and it's more cost-effective since you're not wasting medicine on a digestive system that can't process it efficiently.

What I love about this is that it's accessible right now. You don't need specialised pharmaceutical preparations or underground chemists. You need mushrooms, a lemon, and 15 minutes.

Why I Think This Matters

What strikes me about this whole thing is how it emerged. Not from a research lab or a clinical trial, but from people in encrypted chat groups comparing notes and solving problems in real time. That's how a lot of drug culture innovation actually happens - community-sourced solutions to real-world problems.

Moore also makes a great point: as psychedelic therapy matures and moves toward broader legal access, we need to get way better at understanding how common medications interact with these substances. We've known for years that SSRIs and benzos can affect trips, but GLP-1 drugs are new territory, and millions of people are on them now.

The truth is, our assumptions about dosing and preparation are still playing catch-up with reality. If you're a facilitator, therapist, or guide working with people who are on these medications, this is something you need to know about.

The Practical Side

Now, I should mention: sublingual psilocin isn't without tradeoffs. Psilocin is less stable than psilocybin as it oxidises more easily and requires careful formulation (usually as a stabilised liquid or film).

But Moore's right that these aren't insurmountable problems. There are already underground chemists, harm reduction groups, and even some pharmaceutical startups working on stable psilocin preparations like nasal sprays, tinctures, lozenges, the works.

Final Thoughts

I think this is one of those stories that reveals how messy and interesting the real world of psychedelics is compared to the clean narratives we often see. Rather than clinical trials and government approvals, it's about people navigating real-world problems, sharing information in private channels, and figuring out what actually works.

If you're someone who's on GLP-1 meds and planning to work with mushrooms, just be aware. Your experience might not match what you've read or what worked for you before. Lower your expectations for standard oral dosing, consider alternatives, and maybe chat with someone knowledgeable about this specific interaction.

We're in new territory here. The collision of weight loss medication and psychedelic medicine wasn't on anyone's bingo card five years ago. But that's where we are, and I'm glad people like Moore are paying attention and reporting on it.

Let's keep learning together.