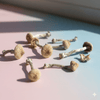

There's a fascinating new study out that's adding to mounting evidence that psilocybin is one of the most effective treatments for OCD.

Published in Comprehensive Psychiatry, researchers led by Luca Pellegrini from the University of Hertfordshire and Imperial College London tried something different. They gave people with OCD a moderate dose of psilocybin instead of the higher doses we usually hear about.

And it worked.

The Problem with Going Big

Most psilocybin research involves doses around 25mg that launch you into a full-blown mystical experience. But if you think about it, that's a tough sell for someone with OCD. These are people who often struggle with a deep fear of losing control. Asking them to surrender to an intense psychedelic journey is like asking someone with a fear of heights to go skydiving.

So Pellegrini's team asked a smarter question: what if you could get the benefits without the overwhelming trip?

The Sweet Spot

They tested this with 19 adults who had moderate to severe OCD. The design was straightforward. Everyone got a 1mg dose first (basically a placebo), then four weeks later, a 10mg dose.

One week after the 10mg dose, participants showed significant improvement on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale - the gold standard for measuring OCD symptoms. The effect was large enough to matter clinically, not just statistically.

But the improvement was almost entirely in compulsions, not obsessions. So people found it easier to resist doing the rituals, even though the intrusive thoughts were still mostly there. It's like psilocybin allowed people to break the behavioural loop without necessarily affecting the mental one.

Building on a Solid Foundation

This isn't the first time scientists have explored psilocybin for OCD, but it's part of a growing body of evidence that's becoming harder to ignore.

The earliest work dates back to 2006, when a small study of just 9 patients found that multiple doses of psilocybin led to acute symptom reductions ranging from 23% to 100% on the YBOCS scale. Despite the tiny sample size, it was safe and showed enough promise to inspire further research.

More recently, we've seen some compelling animal research. A 2024 rodent study found that a single dose of psilocybin (or even whole mushroom extract) produced long-lasting reductions in OCD-like excessive grooming behaviour in mice.

And then there's the ongoing Yale double-blind trial, which is using a more rigorous placebo-controlled design. Early results suggest that a single dose of 0.25 mg/kg of psilocybin, paired with non-directive support, effectively reduces OCD symptoms compared to an active placebo (niacin).

What Pellegrini's work adds to this picture is the sweet spot. A dose high enough to work but low enough to avoid overwhelming someone who's already struggling with control.

Breaking the Loop

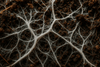

There's also a fascinating neurobiological piece to this puzzle. A recent paper published in Cell this year found something that might help explain why psilocybin works for OCD specifically.

The researchers discovered that psilocybin weakens cortico-cortical feedback loops. Essentially, these are the circuits that keep signals bouncing endlessly around the cortex. At the same time, it strengthens pathways that route sensory information toward subcortical regions, the parts of the brain that turn perception into action.

If you think about OCD as a condition of stuck loops (thoughts that won't stop, rituals that demand repetition) this mechanism makes intuitive sense. Psilocybin might literally be interrupting the neural circuits that keep people trapped in these cycles. It's breaking the feedback loop that makes the same thought or urge come back again and again.

This lines up perfectly with what Pellegrini's team observed. The behavioural loop gets disrupted, even if the thoughts themselves are still there.

Why This Matters

I find this compelling for a few reasons. First, it suggests psilocybin works both psychologically and biologically.

There's even mouse research backing this up. Scientists gave mice psilocybin along with buspirone, a drug that blocks the hallucinogenic effects. The mice still showed reduced compulsive behaviours. The anti-OCD effects seem to operate (at least somewhat) independently of the trip itself.

Second, the tolerability is a huge deal. Nobody had hallucinations. No one had a bad trip. One person had a brief anxiety spike after the low dose, but otherwise, it was smooth sailing. For a population that's often treatment-resistant and afraid of losing control, this is huge.

The Catch

Of course, nothing's perfect. The effect only lasted about a week before fading. By two weeks, the difference between doses wasn't significant anymore. So this wasn't a cure. More like a temporary window of relief. But that's still valuable.

The study also had some design limitations. Everyone got the doses in the same order, so there might be expectation effects at play. And with only 19 participants, we need bigger trials to be sure this holds up.

What Comes Next

The short duration makes me wonder if repeated dosing could be the answer. Could someone take 10mg every few weeks and maintain the benefits? We don't know yet, but it's worth exploring.

I'm also intrigued by the idea of combining this with therapy. The researchers provided emotional support but didn't do active therapy during the sessions. What if you paired this one-week window of reduced compulsions with intensive Exposure and Response Prevention therapy? Could you use that moment when the rituals feel less urgent to build new habits?

The Yale trial is already pairing psilocybin with non-directive support, but I'd love to see what happens with more active interventions during that critical window.

Dose Matters

This study fits into something I've been noticing across psychedelic research: we might be too focused on the heroic dose paradigm. Yes, those profound experiences can be transformative for depression and end-of-life anxiety. But maybe different conditions need different approaches.

For OCD, it seems like you can sidestep the overwhelming trip and still get meaningful relief. That opens doors for more people who might benefit but are understandably hesitant to dive into the deep end.

The fact that depression scores didn't improve in this study is also interesting. Other research shows psilocybin can help depression, but usually at higher doses. This adds to the evidence that dose matters, and different doses might target different symptoms.

Final Thoughts

What Pellegrini and his team have done is expand our toolkit. They've shown that psilocybin's potential isn't one-size-fits-all. A 10mg dose might be perfect for someone who needs help with compulsive behaviours but isn't ready for (or doesn't need) a full psychedelic experience.

And when you layer in the emerging neuroscience about feedback loops and the growing evidence from animal models and controlled trials, a coherent story starts to emerge. Psilocybin might be uniquely suited to breaking the repetitive cycles that define OCD, working at both the neural and behavioral level.

It's early days, and we need more research. But this study is important. It's not just saying "psychedelics work" but "here's how to use them for this specific thing."

That specificity, that nuance, is exactly what we need as this field matures.

Study: "Single-dose (10 mg) psilocybin reduces symptoms in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A pharmacological challenge study" by Luca Pellegrini et al., published in Comprehensive Psychiatry